Title: DEFINING THE POSITA: PTO EXAMINERS MUST DISCLOSE THE RESOLUTION OF THE LEVEL OF ORDINARY SKILL IN THE PERTINENT ART

Gary R. Maze; Richard T. Redano

Examiners often combine references when asserting a claimed invention is obvious because a person of ordinary skill in the art would have reasons to combine prior art reference teachings. They almost never discuss disclose who such a person is.

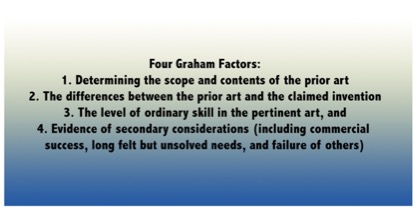

In 1966, the United States Supreme Court, in Graham v. John Deere Co., announced four factors that must be analyzed in determining if a claimed invention is obvious, including the third factor: resolution of the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art. In 2015, Supreme Court, in KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., reaffirmed that the four Graham factors “continue to define the inquiry that controls” obviousness analyses. After KSR, the Federal Circuit repeatedly emphasized that an obviousness determination can be made only after consideration of all four Graham factors.

As obviousness rejections are fact-based, an examiner rejecting a claim as obvious “has the burden of showing a prima facie case of obviousness,” which requires stating the factual bases for the Office Action and relating them to the Graham factors. Only then does the examiner meet the Patent Office’s “obligation to explain adequately the shortcomings it perceives so that the applicant is properly notified and able to respond.”

Although all obviousness assertions require a factual resolution of the third Graham factor, most Office Action obviousness rejections do not disclose any such resolution. However, Applicants should request specification of the requisite resolution of the level of ordinary skill factual bases level.

Some examiners, when challenged, assert that supplying prior art is sufficient. It is not: if anything, supplying citations to prior art only addresses the Graham second factor: the “scope and content of the prior art.” Citation to prior art does not address, for example, active workers’ educational level at the time of invention or whether the person of ordinary skill would have a college degree and, if so, what level, or whether that person has a specific minimum work experience level. Accordingly, identifying only the scope and content of the prior art is mostly insufficient and neither the same as, nor even informative regarding, the level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art.

At times, examiners will also cite to, and/or quote from, MPEP § 2141.03, which relies on the Federal Circuit’s 1983 decision in Chore Time Equipment, Inc. v. Cumberland Corp. to exculpate an examiner’s failure to supply the requisite resolution. However, in Chore-Time “the subject matter of the patent and the prior art were … so easily understandable [that] a factual determination of the level of skill in the art was unnecessary.” In a footnote, the Chore-Time court stated “[neither] simplicity of the invention, or its ready understandability by a judge, constitute evidence of obviousness; rather, an invention may be held to have been either obvious (or nonobvious) without a specific finding of a particular level of skill or the reception of expert testimony on the level of skill where, as here, the prior art itself reflects an appropriate level and a need for such expert testimony has not been shown.”

In view of the Supreme Court’s 2007 KSR ruling, any Patent Office reliance on any 1983 Federal Circuit authority that purportedly permits the circumvention of any one of the Graham factors is ill-advised. More recently, reflecting Chore-Time’s rationale, the Federal Circuit held that “failure to make explicit findings regarding the level of skill in the art does not constitute reversible error when ‘the prior art itself reflects an appropriate level and a need for testimony is not shown.’” This begs a question: how does one know this is true, that there is no such need? Further, an examiner’s incorrect finding with respect to the level of ordinary skill in the art that impacts the ultimate conclusion of obviousness may constitute reversible error. Thus, such findings are still important.

In view of the importance of the third Graham factor, without disclosing the required resolution of the level of ordinary skill in the art the Patent Office fails to meet its burden of making a prima facie case of obviousness, thereby rendering an applicant unable to fully respond to Office Action assertions. Thus, especially when requested by an applicant, an examiner must explicitly disclose the resolution of such a person.

Gary R. Maze, a NAPP member since 2014, is a patent attorney with Maze IP Law, PC in Houston, Texas and has practiced intellectual property law in since 1995. His experience includes preparation and prosecution of patent and trademark applications; patent, trademark, copyright, and trade secret litigation; licensing of intellectual property rights; and legal opinions regarding infringement, enforcement, and/or validity of intellectual property rights. Mr. Maze’s patent prosecution experience includes subsea oil and gas production intervention tools, software and computer related systems, electromechanical devices, and medical devices. Prior to becoming an attorney, Mr. Maze spent over 18 years in the aerospace and computer industries, working in various capacities as an engineer; in software development, both as a developer and as a manager; in marketing, including product line management and heading marketing and technical support; and a small computer business owner.

Gary R. Maze, a NAPP member since 2014, is a patent attorney with Maze IP Law, PC in Houston, Texas and has practiced intellectual property law in since 1995. His experience includes preparation and prosecution of patent and trademark applications; patent, trademark, copyright, and trade secret litigation; licensing of intellectual property rights; and legal opinions regarding infringement, enforcement, and/or validity of intellectual property rights. Mr. Maze’s patent prosecution experience includes subsea oil and gas production intervention tools, software and computer related systems, electromechanical devices, and medical devices. Prior to becoming an attorney, Mr. Maze spent over 18 years in the aerospace and computer industries, working in various capacities as an engineer; in software development, both as a developer and as a manager; in marketing, including product line management and heading marketing and technical support; and a small computer business owner.

Richard T. Redano is a happily retired patent attorney in Knoxville, Tennessee where he has served as an adjunct professor at the University of Tennessee College of Law.

Richard T. Redano is a happily retired patent attorney in Knoxville, Tennessee where he has served as an adjunct professor at the University of Tennessee College of Law.